Even Without "Liberation Day", CoreWeave's Bullishness Was Fleeting (Maybe)

Tariff-induced market pains notwithstanding, the stock might not soar for long.

In the weeks leading up to its IPO, CoreWeave — a cloud computing infrastructure and services provider — wove a somewhat complicated tale. After initially planning to raise $4 billion in funding by offering 49 million shares to the public via the IPO in the $47 to $55 range, the company went on to downsize the offering to 37.5 million shares at $40 to raise $1.5 billion.

After a weak IPO, the stock had a massive pop on the third post-IPO day before President Trump’s “Liberation Day” clarion call on the 2nd of April for increased tariffs on nearly all U.S. trading partners sent markets tumbling. The stock steadily loaded up on bearishness in the after-hours session after a solid market session:

with the stock presently set to possibly close the first week of April anywhere between 15% - 25% above IPO price. Not all of this is necessarily due to “general market concerns”.

Now the company’s business model is thus: the company owns data centres from which it offers clients computing capacity. The clients use this computing capacity to run AI models that serve their clients. The main client to whom it offers its computing capacity is Microsoft, which accounted for 35% and 62% of its revenue in Fiscal Year (“FY” as of December 31) 2023 and 2024 respectively. Three clients accounted for 41%, 73% and 77% of all its revenues from FY 2022 through FY 2024. As of FY 2024, the weighted-average contract term held by clients was approximately four years.

The “Cost of Business”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Nvidia is involved with the company in a number of interesting ways: in April 2023, CoreWeave entered into an agreement with Nvidia to provide the latter with its infrastructure and platform services through fulfilling order forms, meaning that it uses Nvidia chips in its data centres for clients coming through to use those chips. Nvidia has paid the company $320 million till FY 2024 for the provision of services through this route. Nvidia also owns a little under 6% of the company’s stock. However, the $320 million wasn’t consideration offered along with the provisioning of GPUs at no cost; the company has expended vast sums of capital to acquire them and uses only Nvidia GPUs in its data centres. Nvidia also saved the IPO process (which was slipping owing to low interest) by making a $250 million order and “anchoring” the price at $40.

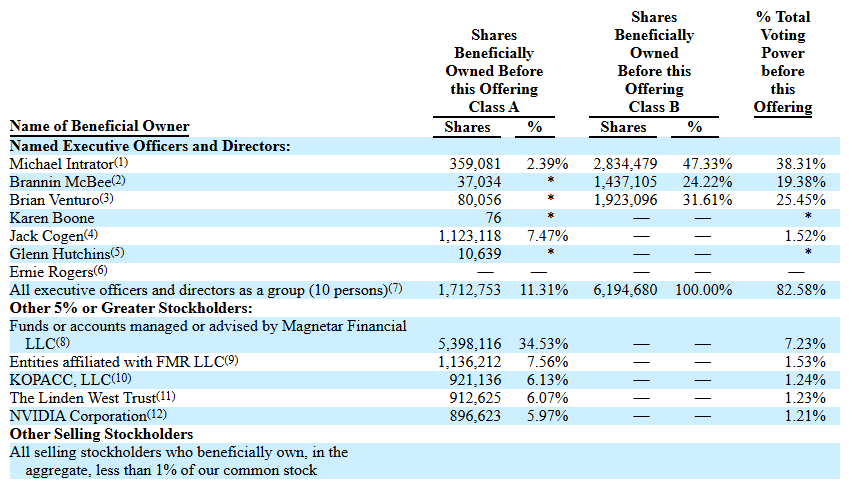

In 2023, CoreWeave raised $2.3 billion in debt led by PE firm Blackstone and hedge fund Magnetar, now the company’s biggest equity investor. For the rest of the cohort, the debt was secured via its purchases GPUs being used as collateral and an actual interest rate above 14%. In 2024, an additional $7 billion in debt was raised from Blackstone, Magnetar and others at a rate of about 11%. As of date, CoreWeave’s CEO Michael Intrator — a one-time salesman of emission credits at Natsource — owns 38% of the company’s stock.

As of at the time of the IPO, Magnetar’s and Fidelity’s various entities are stated in the company’s S-1 filing to own a little under 35% and 8% of the company’s stock respectively:

Stephen Jamison — a former natural gas trader at Morgan Stanley who went solo with his own prop shop Jamison Capital before shutting said shop in 2018 — owns another 6% through the entity KOPACC. Leslie Wexner — former Victoria’s Secret CEO with some connection to Jeffrey Epstein, himself a man of some notoriety both prior to and after his contentious sudden demise in a Riker’s Island prison cell — owns another 6% via the Linden West Trust.

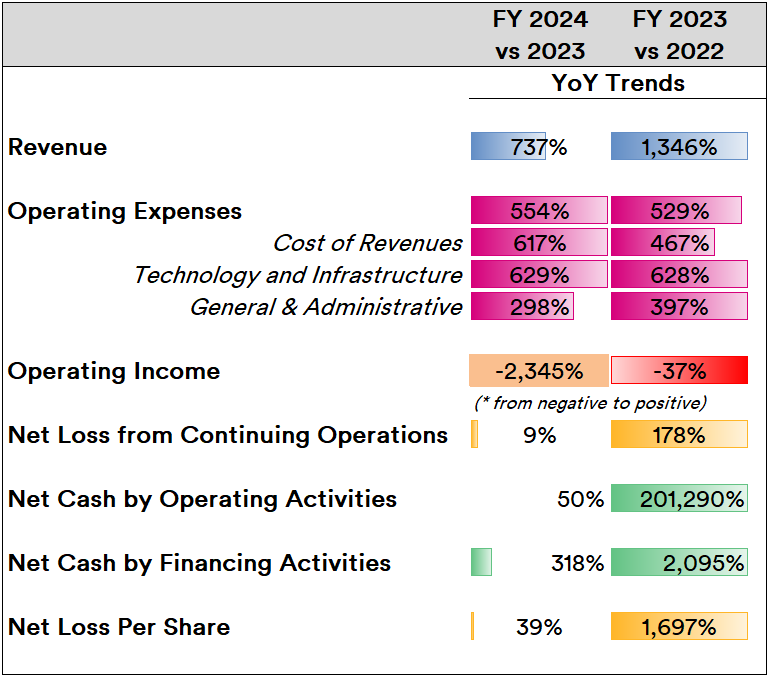

The effect of heavy purchases and debt obligations is writ large upon the company’s balance sheet line item performance trends:

Revenue growth seems to have slowed relative to 2023’s trend while operating income went positive in a rather dramatic fashion. Net cash from operating activities has shown a dramatic drop in growth relative to 2023 (which certainly can be discounted as the company grew from a very small base in the previous FY) but cash via financing remains high. With operating expenses trends continuing to grow in nearly-identical triple-digit percentage terms in both 2024 and 2023, net loss per share continued to grow in FY 2024 (but, again, not as dramatically as it did in the previous FY).

What’s the “Downside”?

On a widely-quoted (and archived) version of its website as well as the sundry press release, the company stated that it charged “80% less than traditional cloud providers”. Its competitors are legion and include the likes of Lambda, Leafcloud, DataCrunch and so forth.

Comparing price charts (accessed as of the 4th of April 2025) for CoreWeave and two of its competitors, this doesn’t quite seem to hold true any more:

The company could leverage its scale of outlay to attract large customers — as its own filings seem to indicate. However, the pricing charts indicate that future growth could only be driven by large clients and the discretionary pricing that comes with them; smaller/other clients are unlikely to hop on, given the wealth of cheaper options.

In FY 2024, the company accrued $1.9 billion in revenue whilst retaining $15.1 billion of remaining performance obligations (RPOs); in itself, it’s a 53% growth over the previous FY wherein it accrued nearly $229 million in revenue. Now, given that the weighted-average contract term is four years, an optimal revenue forecast per year for the next four years on the strength of its obligations alone is around $3.75 billion.

On the other hand, it’s likely to continue expending capital to build out its data centres at substantial cost while effectively spending somewhere around $770 million to $1.1 billion per year in interest to its present creditors. Future debt issuances might also be in order, given the capital-intensive nature of its business. Earnings — at least as recorded as net income/loss and not revenue — are likely to remain fraught for years to come.

Large clients such as Microsoft (which services OpenAI’s computation requirements through CoreWeave’s data centres) are deep-pocketed companies that see a simple value proposition: it is preferable to transform fixed/sunk costs into variable costs. The former entails investing into owned data centres; the latter entails paying CoreWeave’s invoices. If the billed amount in the invoices go too high, it’s better to buy than to rent — and the company’s largest clients have the wherewithal to do that unlike (say) smaller clients. This means there’s an upper bound in the company’s pricing plans while interest expenses chip away at the bottom line.

Next lies an interesting issue that puts a question mark on the entire AI industry’s forecast on a near-philosophical basis: the advent of open-source AI — perhaps best exemplified by the hype around DeepSeek in China.

Note #1: DeepSeek was covered in detail in my articles published in Leverage Shares, SeekingAlpha and TrackInsight.

While DeepSeek was initially “open-weight” and not “open-source”, it has begun to release code repositories to the public. Of course, DeepSeek’s models referenced the open-source work of China-based Alibaba and U.S.-based Meta to go on to outperform Microsoft-partnered OpenAI. In turn, Alibaba's Qwen model itself was a “teacher” to Stanford University's S1 model that also distilled from Google’s Gemini Thinking Experimental model to outperform OpenAI's model on a set of curated questions.

Early in March, Alibaba stated that its open-source QwQ-32B reasoning model surpassed the performance of DeepSeek's R1 in areas such as mathematics, coding and general problem-solving, despite its relatively modest 32 billion parameters to DeepSeek's 671 billion. QwQ-32B also was stated to outperform against OpenAI’s o1-mini, which was built with 100 billion parameters. Following DeepSeek and Alibaba’s lead, China’s search giant Baidu stated that its latest reasoning model — Ernie 4.5 — would be open-source from the 30th of June, which marked a massive departure from the company's long-held OpenAI-like stance on closed-source development of AI.

Note #2: Baidu’s recent earnings and subsequent rising investor interest was covered in detail in my articles published in Leverage Shares and SeekingAlpha.

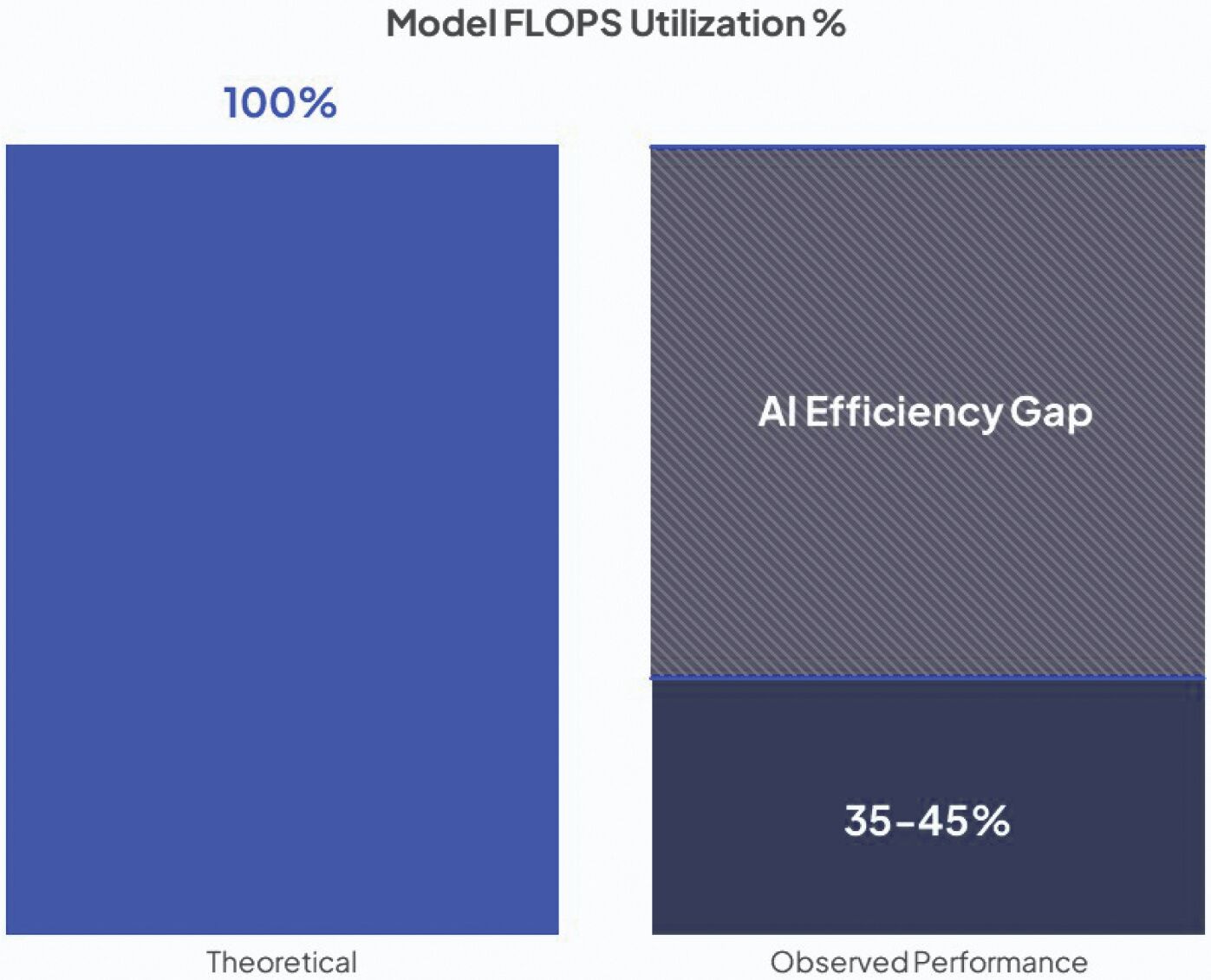

Herein lies the rub when it comes to closed-source AI models currently in vogue and heavily deployed via corporate data centres for corporate purposes: they’re heavily inefficient. CoreWeave highlighted in its filing leading up to its IPO that scheduling AI workloads on infrastructure at scale is complex and maximizing the compute potential of infrastructure grows increasingly difficult as the scale increases. The theoretical throughput of compute infrastructure is measured in terms of Maximum FLOPS Utilization % (or MFU) — wherein “FLOPS” stands for “Floating Point Operations per Second” — is almost never achieved in reality, thus creating an “AI Efficiency Gap”.

More than half of scaled compute infrastructure is effectively paid for but not realized in terms of delivering results. There are, of course, means of achieving optimization. As the Substack article published last June indicated, AMD’s CPUs continue to be in play within datacenters by having the complexities of high computation handled via software methods that essentially break down a problem set into smaller “chunks” that could be handled by less-powerful hardware, thereby bringing in a form of “mixed-mode optimization” in deployed hardware profiles of relatively lower complexity (and cost).

If a real-world (read: easy) analogy were necessary: imagine an operation between two very large numbers that would cause a standard TI calculator made for high-school students to throw out an error. If said numbers were reduced in “size” via a common divisor, after which the operation is carried out and then the divisor is applied upon the result either separately or with a trusty pen and paper, the problem has been solved (albeit with a few extra steps).

Now, if it were possible to reprogram the calculator’s circuits independent of the manufacturer, the result could be a game changer that threatens the calculator industry as a whole, especially if adopted en masse. DeepSeek’s success has one such facet hidden away: it has been reported that DeepSeek managed to achieve its OpenAI-approximating results — despite not having the H100 GPUs that Microsoft/CoreWeave can provision for OpenAI due to sanctions on China — by dropping down to PTX, a low-level instruction set for Nvidia GPUs that is much like assembly language, to program 20 of the 132 processing units on China-oriented lower-complexity H800 GPUs specifically to manage cross-chip communications to deliver the optimization needed to achieve near-parity in results achieved with vastly-superior chips. Essentially, the “closed box” that is the calculator (or “corporate LLM”) has essentially been opened, found wanting by the community of users, and vastly improved at the calculator (or “AI”) industry’s expense.

With code repositories increasingly being unlocked and a thousand LLMs (“Large Language Models”) possibly blooming all over the world in a few years, it’s possible that there will be a glut of compute infrastructure available on demand all over the world. In such a scenario, CoreWeave — which is already at twice the pricing level as some of its competitors — will be hard-pressed to drop its price in order to remain a viable service provider or risk losing clients at the end of the contract.

In other words, the open-source innovations are potentially poised to upend the entire AI industry, along with its costly and inefficient “economies of stack”. We might be standing at the cusp of glorious evolution.

Why the Stock’s Uptrend is Unlikely to Last

With around 10% of its shares outstanding offered to the public via the IPO and, of course, its near-exclusive association with a premium chipmaker and a premium computation provider, much of the interest around the stock is from investors looking to round out their overall exposure to the AI/semiconductor space. Plus, given the fact that it is closely associated with Nvidia and Microsoft gives it a certain sheen a la Super Micro (or “Supermicro”) among some retail investors.

Note # 3: Incidentally, Super Micro had a recent dramatic turn of events regarding its earnings, which were delayed to the brink of delisting before a last-minute filing. Read the analysis of the long-delayed earnings reports here on Leverage Shares and here on SeekingAlpha.

But much like Super Micro, it is distinct from those it associates with simply by virtue of there being a deep well of competitors offering services at highly competitive rates, while being entirely dependent on those it’s ostensibly partnered. With a fundamental change in the industry over the long run and limited appeal among the larger client market owing to its (stated) pricing structure, the stock’s surge is unlikely to last after primary shareholders have either offloaded or adjusted their shareholding patterns.

Neither Microsoft nor Nvidia has a massive dependence on CoreWeave’s success. In fact, as far as Nvidia is concerned, this might have been one hell of a deal: if it were to be assumed that at least 60% of the nearly $10 billion of debt raised by CoreWeave was expended in the purchase of GPUs, then the chipmaker indirectly netted around $6 billion in chip sales indirectly via its (till date) commitment of $570 million — essentially a 10X return on investment.

Not too shabby.

In March 2025, I was quoted in TheStreet over strengthening trends seen in U.S.-listed Chinese stocks eyeing their prospects in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX). Read the full rationale of my commentary here. Also, click here to read the full context of the commentary made about Tesla and crypto markets that appeared on Reuters and FXStreet respectively.

For a list of all articles ever published on Substack, click here.