India and the AI Arms Race: An Arsenal Builds

While India's current position is diminutive, the groundwork prepares it for the Top 3 podium by the end of this decade.

On the 20th of this month, I received a message from South China Morning Post with questions about India’s place in the AI arms race as well as that of other nations in Asia. No idea when or which article my comments will be included in but, in the meantime, here’s the expanded background that shaped my opinions on this.

Amid the global ChatGPT frenzy, the competition is on between China and US firms, but Indian startups have also risen to be a formidable force in the past few years. Where do you see India on the map of the current AI global arms race?

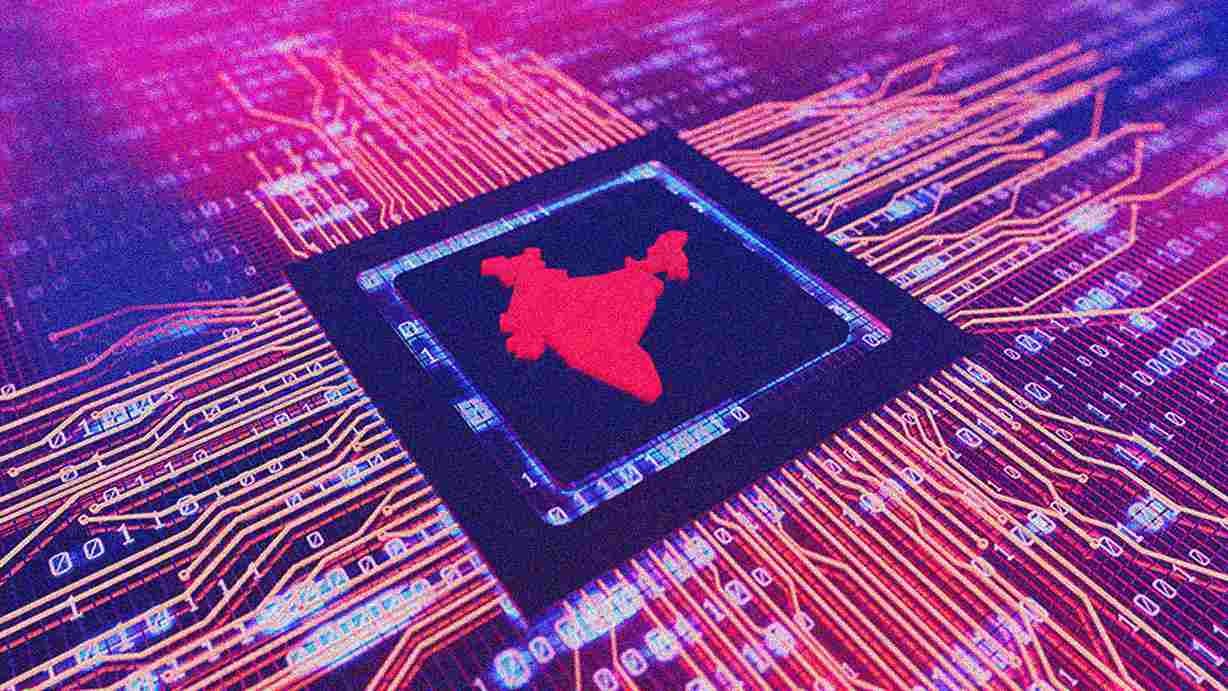

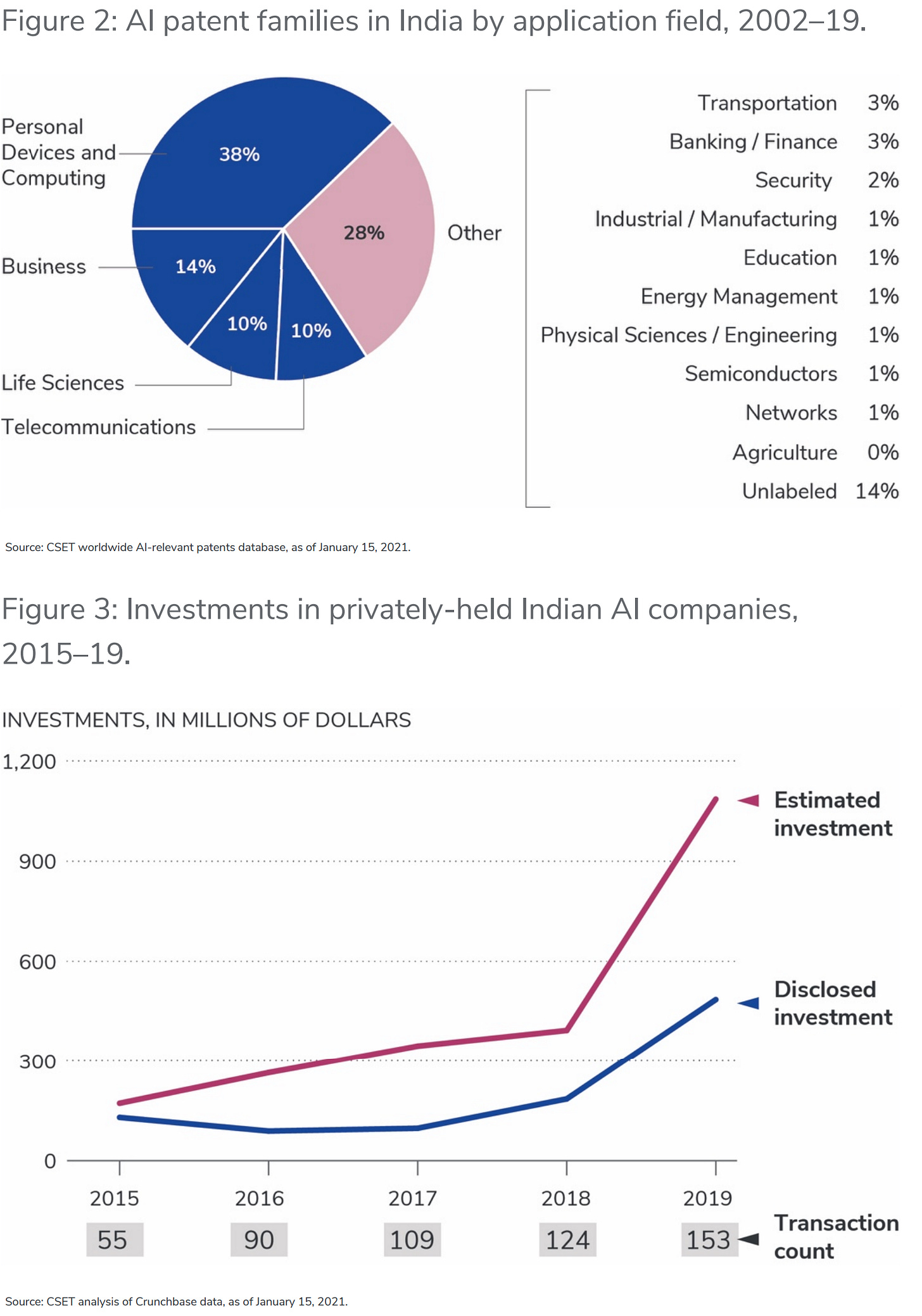

As per a brief published last year by the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) at the University of Georgetown, private-market investment in India’s 361 privately-owned AI companies witnessed a steady growth between 2015 and 2018, after which it nearly tripled in dollar value: the percentage jump in India’s estimated investments in 2019 alone was higher than that of any country, including the United States and China. More than 70% of India’s AI patents relate to personal devices and computing, business, telecommunications, and life sciences — areas of traditional strength for India’s technology sector.

Furthermore, investments in Indian AI firms are already estimated to have crossed the billion dollar mark in a single year by 2019.

India produces almost twice as many master’s level engineering graduates as the United States and is second only to China. Over 96% of graduates of Master’s leveltea engineering programs in Indian universities have exposure to AI-related fields.

However, at the doctoral level, this share plummets to single-digit percentages. As it stands, Indian universities produce less than one-third as many PhDs as the United States. Only 2.5% of Indian universities have doctoral programs. The reason for this is multi-factored but it could be argued that quantity doesn’t imply quality: the resulting output is laying the groundwork for future academic research and evolving in their approach to contributing to industry development.

Further evidencing this assertion is that, despite barriers reportedly faced by Indian scientists such as lack of funding for international work, differing academic standards and bias against scholars from economically developing countries as well as macro factors such as low R&D as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) or low gross expenditure on R&D per researcher, Indian academic research in AI was already ranked fourth globally by 2019 and well-supported by historically-strong collaboration with the U.S. and U.K. (2nd and 3rd, respectively).

India’s standalone research stands tall in traditional AI fundamentals such as pattern recognition and computer vision:

Meanwhile, it has been tapping collaborations with AI’s ostensible leader — China — in relatively-deficient areas: a net 627% increase in collaborations with Chinese researchers in fields such as data mining, AI and optimization has been estimated for the same period.

To further buttress the strong developments in this field where India had no AI-relevant patents prior to 2002 — as compared to the U.S. (which is estimated to have started in the late seventies) and China (mid-nineties) — the Indian government has proposed three centres of excellence to be set up in top universities for the vision of “Make AI in India” and “Make AI work for India” in its latest Budget through which industry players will also enter partnerships in conducting interdisciplinary research. Furthermore, unlike in the rest of the world — which has only witnessed patchwork legislative interventions — the upcoming Digital India Act will enforce guidelines that aims to foster innovation and creativity while offering ethical and responsible solutions to users. Given that AI is here to stay, the fact that the Indian government is keenly aware of the ramifications of AI adoption and is envisioning robust mechanisms indicates that it perceives ethical challenges far more keenly than other governments have till date.

Given that India doesn’t currently have a domestic manufacturing capacity for AI chips, Indian AI companies and researchers depend on market cloud computing to support their computing needs. India is one of the world’s fastest-growing cloud markets with demand expected to grow at double-digit rates. To democratize and ease access, Indian government’s top think tank — Niti Aayog — has proposed the expenditure of about a billion U.S. dollars in the 3-phase construction of AIRAWAT, an AI-specific cloud computing network for domestic consumption, in 2020.

It can be expected that this estimate will be revised upwards and the network will commence with implementation after the passing of the Digital India Act.

In addition, the domestic availability of chip manufacturing may not be far behind: Indian conglomerate Vedanta Resources, in a joint venture with Foxconn, plans to set up a display fabrication unit, integrated semiconductor fabrication unit and outsourced semiconductor assembly and test facility with an investment of $20 billion in India while availing production-linked incentives (PLIs) from the government. Without going into details, Vedanta-Foxconn confirmed that they have an agreement with a technology partner to transfer technology with licenses. The window for other players interested in government incentives will remain open till the end of 2024.

Meanwhile, domestic manufacturing of semiconductor chips have already begun: Indian manufacturer Polymatech announced the commencement of domestic production of opto-semiconductors and memory modules at the rate of 400,000 chips per day in October 2022 which will shortly ramp up to 1 million per day. The company — originally a joint Japanese-Malaysian concern whose shares were fully transferred to an Indian business in 2018 — aims to become one of Asia’s largest chipmakers by 2025 and is aiming for an annual revenue of $12 billion by 2030.

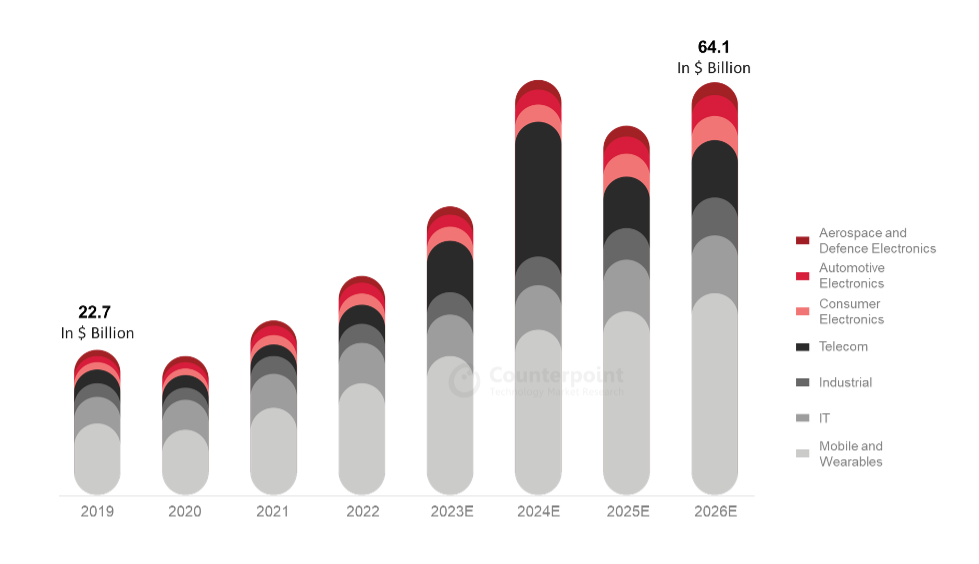

Indian semiconductor industry is expected to see a three-fold increase from 2019 levels to over $64 billion by 2026, with local sourcing already accounting for around 10% of the overall market in 2022.

The resulting ramp-up in access for domestic firms will likely affirm the nation’s path to “Aatmanirbharta” (self-reliance) — a key national objective — by the end of the decade.

Generative AI is expected to have a minimal impact in India’s $245-billion tech services industry, with around 300,000 people in sales and support functions. Of this, around 50,000 to 60,000 employees — or about 1% — can be impacted over the next 3-5 years, as per a recent study. Thus, Generative AI represents strong upward potential for startups and aspiring tech firms in carving out a distinctive space for themselves. India is home to around 10% of the world’s pure-play generative AI startups and have raised tens of millions of dollars in funding since 2019.

All factors considered, India’s position in the current AI arms race is that of an “underrated entrant” with an impactful proportion of domestic research, a steadily-increasing availability in domestic hardware, projected ramp-up in domestic computing infrastructure availability, keen demand in solutions from both domestic and global sources and a strong moat for maintaining indigenous capabilities. It can be expected that the next 5-7 years will see Indian firms stealing a march into the Top 3 podium (at least) and the gap between the three positions drawing much tighter than it is currently.

Other than India, do you see a similar AI wave in other parts of Asia, such as Southeast Asia?

Southeast Asia, in fact, has seen skyrocketing investments — in excess of $10 billion — into the AI wave since 2010.

Of all ASEAN nations, Singapore has seen the largest amount of investments, where the deal flow has been 10-12 times greater than in Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand combined. Foreign investments form about 60-70% of all investments in the region.

In this mix, Chinese firms represent the largest share by transaction value while American firms dominate transaction volumes.

However, it bears noting that 40% of Chinese capital flows into ASEAN’s AI market between 2013 and 2021 was a single deal - Chinese streaming platform JOYY (formerly known as YY) acquiring Singapore-based BIGO Technology for $1.45 billion in 2019. Overall, the AI space here is driven by more traditional AI-driven/Big Tech-dependent applications as opposed to Generative AI. For example, Thailand’s Sertis has ties with Google, Microsoft, and AWS for its AI-powered face recognition technology while Singapore-based ViSenze offers picture search and recommendation engine for shopping via “native” integration with Samsung, Huawei, Vivo, Oppo, and LG phones while hosted on Amazon cloud services. In that regard, they lie along the axis of the AI startup ecosystem in the Western Hemisphere and will continue to be a healthy part of the AI wave.

On the other hand — on the chipmaking front — most of ASEAN’s hardware manufacturing lies “midstream” between Chinese suppliers and global hardware majors. Networking and memory components form the biggest share of the pie.

Overall, the likelihood of an independent chipmaker from this region seems to be slim with established Korean chipmakers — Rebellions, Sapeon Korea, FuriosaAI, et al — and rising Indian chipmakers likely to cause different (and additional) forms of pressures on the industry when backed by strong national incentives. A collaborative Indo-Korean axis of chipmakers under holistic technology sharing principles has immense potential in upending the current status quo which sees primacy enshrined within Western Hemisphere majors.

There has been a “New India” theme in the past couple of articles. Click here to read more on overall macroeconomic trends that point to the coming few years becoming “New India’s” decade. Next, in light of a big announcement by GE Aerospace, click here for a full overview of how the race for making a jet engine in India is shaping up.

Incidentally, a “Indo-Korean” axis needn’t be limited just to AI: as an earlier series comparing the two countries’ military aircraft industries indicated (here’s Part 1 and Part 2), there’s substantial potential in other areas as well.

Other such expansions of my commentary include a discussion about Big Tech’s dominance over AI evolution made to Bloomberg, Korea’s market evolution and lessons on short-selling (courtesy Adani) made to “Chosun Ilbo”, and the American banking crisis made to MarketWatch.

For a “Big Read” on matters not related to market events, the “Dharma” series traces the evolution of Eastern philosophy and India’s core position in it. Click here for the first part and proceed thenceforth. Finally, click here for a list of all articles published till date.